I was speaking with a customer the other day about modifications on his engine and I brought up the possibilities of adding a throttle body injection system. He laughed as he told me absolutely not, “I know how to work on a carburetor and I know how to start a carbureted car”. Fair enough and certainly a respectable response. There are some very distinct differences between an engine that is fuel injected and one that is carbureted. That may sound like a “duh” statement but how much thought have you really put into making the decision on how you will deliver fuel to your engine. All engines require three things to run, when you take away all the electronics and the processor and the shielded circuits from the new “modern” vehicles the engine will still need just three basic things to operate and run; air, fuel and ignition.

Your engine runs more on air than it does fuel, you need the fuel, don’t get me wrong, but air is a major contributing factor to engine performance. For many years aftermarket performance air filters, such as K&N filters, have been very popular with performance-minded individuals. These filters provide very good filtration but allow considerably more air flow than the factory filter. Even if you do not want to invest in a K&N Filtration system, buy a quality air filter for your car, dust and debris destroy and engine and many aftermarket air filters do not have the same micron rating as the factory filter, in addition, many aftermarket filters are not built as strong and will be sucked into the air cleaner housing allowing huge amounts of unfiltered air into the engine without your knowledge. The new car offerings from several manufacturers are trying to reach customers performance and economy expectations by adding turbochargers on smaller engines. Top Fuel dragsters and Funny cars use blowers, a large number of race cars use superchargers (blowers) and turbochargers when looking for increased raw horsepower from their engines. Air is important and the more you can get into the engine the more power you can make. The recommended air/fuel ratio for a complete efficient combustion of the fuel is 14.7:1. That number does vary slightly based on the quality and the type of fuel, 14.7:1 for normal pump gas, 6.4:1 for alcohol and 14.5:1 for diesel fuel. Normal pump gas will add to that variable when taking the quality of fuel and octane rating into account. To sum it up though, you need between 13 and 14 times as much air as you do fuel to run an engine efficiently. We aren’t using “efficiently” in this discussion as a reference to fuel economy, we are using it as a measure of how well the engine is performing to burn the fuel completely. More air, more fuel, bigger boom. Try this, break out your old oxy-acetylene cutting torch and fire it up, get a good weld flame and throttle the oxygen lever, gets super hot doesn’t it. Leaning the engine out, using more air than necessary, will make for a hot fire in the combustion chamber but, just like the cutting torch, you will begin to cause damage to the valves and pistons due to the excessive heat. Run the mixture too rich and the fire cools and the engine makes less power and begins to become polluted with unburned fuel which, ultimately, creates soot and carbon build up that robs power even after the correction to air/fuel mixture has been made. Adding a turbocharger or blower compresses air into the cylinder, making the air more dense, with a 14.7:1 air/fuel ratio you will still have complete combustion but you will also probably end up with an engine “ping” or spark knock. Now, there are several other factors that may contribute to the spark knock, like ignition or valve timing, but we aren’t going into that realm in this post. When compressing the air into the combustion chamber you raise the peak pressure of the cylinder which creates the knock. Mixing a little more fuel in will still provide for complete combustion but will be a slightly cooler explosion reducing the occurrence of spark knock.

Many fuels have been used over the years to power various types of engines, water being among them ( think steam locomotive). We are talking about volatile fuels though, Nitro-methane, alcohol, gasoline. There are several variations of fuels used to power internal combustion engines (I.C.E.). The engines are built for the specific fuel they will be used to power the unit. Delivery is important, hence the purpose of this post, when relative to the power the builder is expecting to achieve from the engine and each method has its own pros and cons. While we have briefly explained the importance of air, fuel delivery is somewhat more complex. The amount of fuel that needs to be delivered can be affected by the size of the fuel lines, the pressure and flow of the pump and by the design of the engine as well. A Top Fuel dragster uses 4-5 gallons of fuel for each ¼ mile pass and over 10 gallons total during a run when factoring in the burn out at the beginning of the race to the breakdown at the end. Delivery of that much fuel is akin to pouring a bucket of fuel into the engine. I’m not altogether sure I could empty a 5-gallon bucket of fuel, controlled, in less than five seconds, that is a huge achievement in fuel control. Looking at another area of performance, F1 cars are limited to 100kg of fuel per race, approx. 36 gallons. The engineers for the engines in these cars have a huge task, how to meter the fuel delivery for optimum performance and to achieve the economy needed to complete the race. Climate, altitude, track surface and the amount of cautions all play into the equation. Weight is also a critical factor in these vehicles, more weight equals a slower car that will require more fuel to provide the desired performance. Weight is a factor in nearly every automobile racing event and measuring the fuel to “just enough” is crucial when races are won or lost by fractions of a second. Manufacturers also look at how the fuel will be metered to balance the same variables that F1 is looking at to balance power and economy. This is obvious when you look at the amount of lightweight components used in cars, lighter weight equals, in this case, better fuel economy which helps manufacturers reach the C.A.F.E. standards sets by the Government. We may not like it but all those temporary spare, space saving, spares are used for that reason, a large number of new cars don’t even have a spare tire and have been replaced with 12-volt compressors and can of fix-a-flat. Thinner sheet metal, more plastic materials, cheaper window regulators, all factor into the weight calculations used when trying to reach a myriad of Government standards. Next time you are annoyed by how cheap the materials used in your new modern car seems to be, write your representative in Washington, he/she has had as much to do with it as the manufacturer of your car. Weight and performance become part of the equation when choosing your method of fuel delivery and needs to be balanced, again, to meet the needs of the vehicle and your desired performance level.

Ignition systems seem fairly straight forward, make a spark and the fuel/air mixture explodes creating the energy and opposing force to push the piston down in the cylinder. Seems simple but we still have to look at the same things we did before. Air, fuel and ignition are all related and each has to be balanced with the other to reach the desired effects. The earliest systems were magneto type and produced a very high voltage spark, typically higher than what a modern distributor type ignition system does. Magneto type ignitions are similar to those found in many lawnmower or outboard boat engines now. The primary difference, other than exceptionally high spark output, 20,000 volts in some cases, is that a magneto does not require a battery or outside power source to operate. An automotive magneto, instead, uses a distributor (not so in small engines and outboards) similar to what we are familiar with but has a generator built into it using the magnets to build the energy for the spark, hence the name “magneto”. As automobile electrical systems evolved so did their ignition systems, with the use of more sophisticated batteries and the addition of better generator/alternator charging systems the complexity of the magneto was traded for a simpler distributor design using breaker points, and a condenser, much like the magneto, but uses an ignition coil to supply the spark and the engine mounted charging system components to provide the energy to charge the coil. This system worked well and produced very little feedback, that would interfere with electrical accessories, such as radios. To increase performance distributors were equipped with two sets of ignition points, this improved the performance of the breaker points at higher engine speeds to guarantee a hot spark. Obviously, we have evolved from there and use hall effect style switches to electronically communicate with the engine control systems to provide a spark. Early electronic ignition systems used essentially the same type distributor we had become used to and installed the hall effect and pick up in place of the points. Current model vehicles typically use either a crankshaft or camshaft position sensor to communicate with the engine controls for proper spark timing and use multiple coils to provide spark more directly to the spark plug.

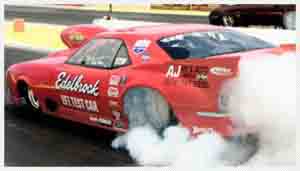

Now, you may have more questions now than you did before this post, I understand that. In the next post, we will look at the distinct differences between carburetors and the different fuel injection systems but you, the hobbyist, enthusiast or just someone who wants better performance, or fuel economy from their classic car need to consider all the variables outlined here. It all may seem confusing but only when you have taken the time to ensure that all of the systems work together can you realize your goal. For instance, it personally makes no sense at all to upgrade your engine to a fuel injection system only to use a breaker point ignition system, you are not going to achieve the precise spark control necessary to operate with the efficiency expected from an injected vehicle and therefore will be disappointed with the results. Often times, that is where you will find the negative on many products, from someone that really did not do their research and make sure that all the components work together. Due to circumstances of their own making, all of a sudden the product sucks and the individual fails to understand, or won’t admit, that they failed, not the product. This is also not the area to go cheap, spending the extra few dollars necessary to purchase quality components from reputable vendors and reputable companies, such as Edelbrock, Holley, MSD, Mallory, K&N and Moroso, just to name a few will decrease the possibility of a premature part failure. Also, buying from a reputable company gives you a resource to talk to when you do have difficulties. There is a huge amount of quality aftermarket equipment available on Amazon and eBay, and I’m not here to bash them, but if you run into a problem you are less likely to receive professional assistance from those vendors. What you are trying to do is make life easier on yourself and others that may drive your car, not more difficult. A few vendors we may recommend to source some of the items you may need to achieve your performance goals are Old Dog Street Rods, Jeg’s and Summit Racing.

Look forward to the conclusion of this post in the next few weeks, in the meantime check out a few of these links that will help you understand the fuel injection systems, air induction systems and ignition systems available for your classic car, muscle car, street or rat rod.

Edelbrock Electronic fuel injection installation and performance.

MSD Ignition systems, ignition systems 101

Holley Avenger/Dominator Fuel Injection systems.

Mallory conversion to electronic ignition